We set off early this morning for the neighboring town of San Miguel de Escobar. There, we met Manuel and Angela. Manuel is a coffee farmer. Angela is our interpreter since Manuel does not speak English and many of us don’t speak Spanish. Manuel works for a cooperative of coffee growers in San Miguel de Escobar and also with De La Gente, which is a coffee NGO (non-governmental organization). The Guatemalan government supports the coffee farmers throughout Guatemala in a variety of regions as a way to invest in the overall economy of the country - it lifts all people through a domino effect.

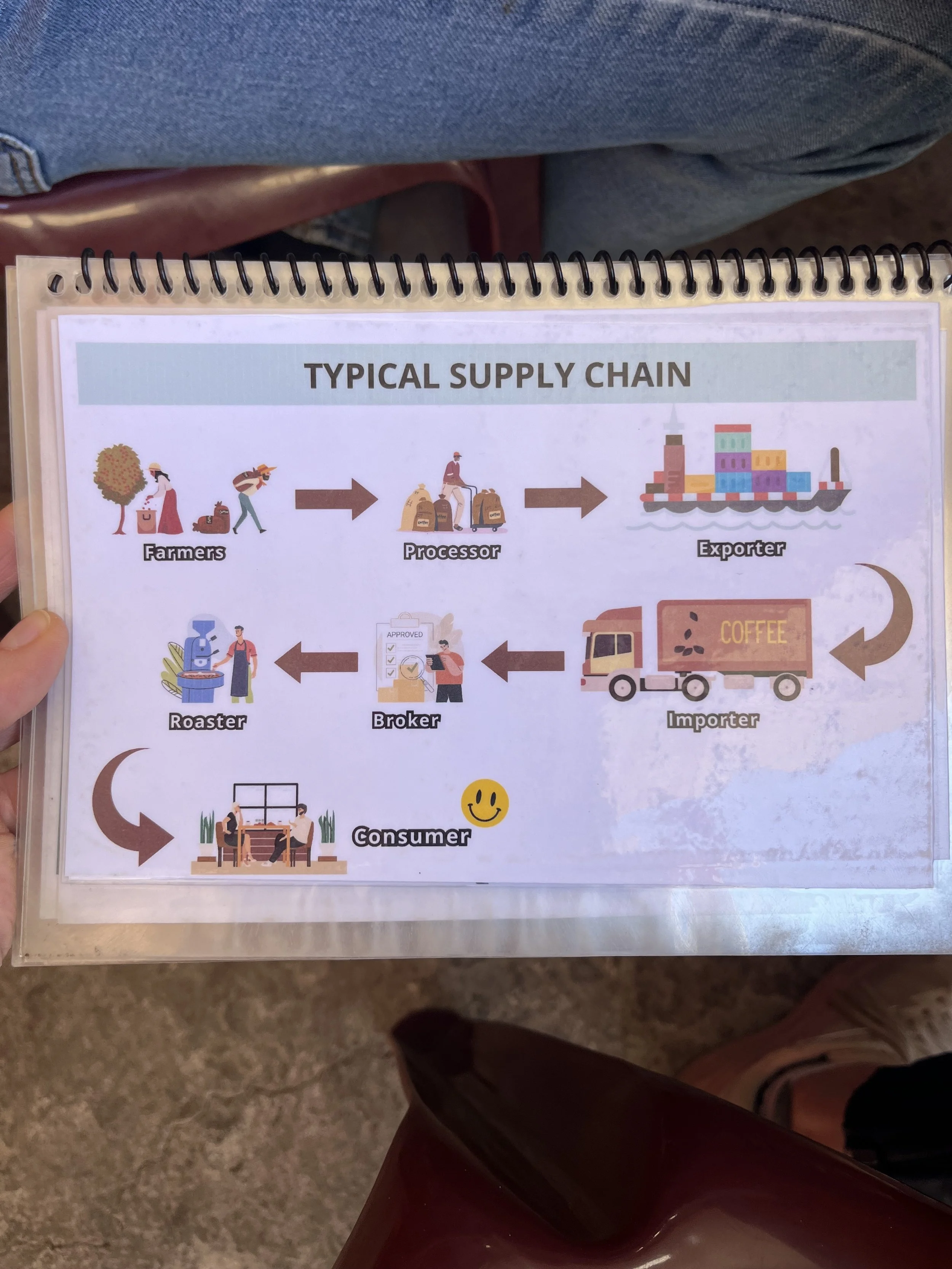

Coffee is a massive global industry valued at over $460 billion in 2020. Over 90% of the world’s coffee is produced in developing countries, while the majority of consumption takes place in developed, industrial countries, a reality fueled by normalized exploitative practices. The conventional global supply chain allows for coffee to be a commodity of enjoyment, daily ritual, and community for billions of drinkers around the world, while too often it is a source of economic precarity for those who cultivate it.

Coffee has played a major role in Guatemala’s economy since the late 1800s, serving as the backbone of the country’s GDP for nearly a century. While Guatemala’s economy is more diversified today, coffee remains one of the top exports by value. Within Guatemala, there are approximately 125,000 coffee farmers, 97% of whom are small-scale producers that account for nearly 45% of the country’s production. Large-scale plantations, which represent only 3% of Guatemala’s farmers, are producing more than half of the coffee in the country. Small-scale producers, like Manuel and the cooperative he is a part of (keep reading), despite intergenerational experience and expertise in the industry, continue to be more susceptible to price fluctuations, climate change, and exploitative supply chains.

In 2005, Franklin Voorhes was volunteering in Guatemala when he met coffee farmers from the town of San Miguel Escobar who were organizing to make cultivating coffee a sustainable livelihood. Franklin was intrigued and inspired by their vision and wanted to be part of helping them improve their quality of life as small-scale producers. Together with seven coffee producers, they started processing their coffee and looking for markets for high-quality green and roasted coffee. Out of that partnership and many subsequent discussions and experiments, an organization called (at the time) As Green As It Gets emerged, and the cooperative is now known as the Coffee Growers of San Miguel Escobar.

They worked collaboratively for several years, improving the quality of farmers’ coffee by exploring various processing techniques while simultaneously systematizing and structuring the cooperative. Over time, they wanted to educate and create awareness among tourists arriving in Antigua about coffee production, so they developed a tour where small-scale coffee producers would share their expertise, culture, and hopes for the industry with visitors. Tourism has since evolved into a thriving element of their work.

In 2014, “As Green As It Gets” became “De La Gente” (meaning Of the People or By the People), a name that describes who they are, who they serve, and who benefits from their work. They specifically decided to confront issues and injustices within the coffee supply chain and related challenges that producers face. At that time, they incorporated more cooperatives on a larger scale, choosing to accompany and assist them in becoming sustainable and thriving coffee producers.

Today, De La Gente works in partnership with four coffee-growing regions, nine cooperatives total, representing over 140 small-scale coffee producers, and channels nearly $350,000 each year to farming communities in sales alone. They have been recognized for the quality of their coffee, their transparent relationships with the cooperatives they partner with, and the immersive opportunities they offer within those communities.

Our group walked about 20 minutes up the volcano from Manuel's house, into the coffee fields. All around us, the three volcanoes were erupting continuously with Fuego. Rabbi Flip doesn’t know yet that I signed us up to hike the volcano on Shabbat. Shhhh… don’t tell!

Coffee leaf rust is a fungus that infects the coffee tree and causes it to lose its leaves and die slowly. The trees that are part of the cooperative are treated with organic treatment fertilizer, limestone on the trunk of the plant, and sprayed with copper to prevent the fungus. Additionally, when the coffee tree has too much shade, it is more susceptible to fungus. Coffee needs shade to grow, but it has to be the right balance. The beans go from green to yellow to orange and then finally to red, and that’s when they’re ripe. The black ones don’t have a coffee bean inside. Some companies blend the black beans anyway with the green, not yet ripe beans, to make instant coffee and then treat it with other flavorings. Rabbi Flip and I are already feeling the pressure to up our coffee game!

Inside each red coffee cherry, there are two coffee beans and a liquid that they call coffee honey. If you chew the red skin, it tastes like a cherry flavor. Occasionally, the berries have just one coffee bean inside, and those actually have a really good flavor, but it’s rare to find coffee that’s made only from the berries with one coffee bean.

I’ll admit that I have developed a fondness for my two coffee beans and have promised them that I will never drink instant again. It seems the least I can do.

It takes a total of three years to get the first harvest from a coffee tree. When the coffee trees start to produce, they create a white flower that smells like jasmine. The jasmine smell attracts the bees that come to pollinate the flowers, then the coffee cherries begin to ripen. Currently, we are at 1600 m above sea level. Coffee can be harvested up to 2000 m above sea level - the higher up you go, the stronger the coffee. While there is only one coffee harvest season per year, they are actually picked at three different times during the season due to the cherries ripening at different times.

The unroasted beans are green, and they are exported that way. De la Gente has a US roaster located in Cincinnati, and when you buy coffee from De La Gente, it is roasted and shipped to you immediately because once coffee beans are roasted, they have a shorter shelf life. Longer roast = darker roast/color. Manuel’s wife, Rocio, roasts the green coffee beans and then grinds them on a grinder given to her by Manuel’s mother as a wedding gift, which is customary in a Guatemalan marriage. (Audrey… where is my coffee grinder?)

Basically, if you want really good coffee, you need to buy from De La Gente or a reputable cooperative with strict standards on farming and sorting. You need to buy it immediately after it is roasted and grind it yourself just before you brew. Basically, Rabbi Flip and I have been drinking the “Boone’s Farm” of coffee and had no idea. (Apologies to those who like “Boone’s Farm”. We will be doubling your annual support😉.) Also… Guatemalans do not make or drink anything but caffeinated coffee. Apparently, we shouldn’t either!

P.S. There’s also now a female farmers’ cooperative, women and their daughters making coffee as part of De La Gente. And if you are eager to drink this amazing coffee, head to B’s Salty and Sweet in Colombia, TN, where Micah members David and Bethany Boran serve it every day!